Role of Molecular Traits and Drug Expectations for COVID-19

Abstract

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, which initially began in China, has spread to many countries across the world and caused a public health emergency of international concern with a keep increasing confirmed cases every day. Possible natural source of the virus has been reported as bats. Genome analysis and structural biotechnology reveal the mechanisms of the virus infecting human beings by the interaction between spike protein and Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2(ACE2) receptor. Research on vaccines and special medicine have been in full swing in the past few months. Here, this paper systematically reviews recent discoveries about the COVID-19 in some aspects and propose possible solutions with bioinformatics methods.

1 Background

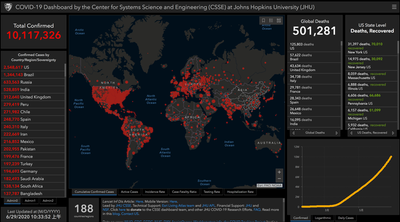

On 31 December 2019, the WHO China Country Office was informed of cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology (unknown cause) detected in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China. As of 3 January 2020, a total of 44 patients with pneumonia of unknown etiology have been reported to WHO by the national authorities in China. Of the 44 cases reported, 11 are severely ill, while the remaining 33 patients are in stable condition. Soon after, the disease was named after COVID-19 and a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is responsible for the fatal disease. With the explosive increase of confirmed cases, the WHO declared this outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020. According to COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU), as of June 29, 2020, the cumulative number of confirmed cases worldwide has reached 10,117,326 with a global deaths of 501,281 (Figure 1).

The high infectivity and lethality of the disease has raised great public concern about the pandemic and once again reminded global citizens of the necessity of social distancing and self-isolation since there’s no specific drugs or vaccines to deal with the virus so far.

2 Coronaviruses in Virology

Viruses are non-cellular structured microorganisms with small size and no complete cell structure. There is only one kind of nucleic acid (RNA or DNA) as genetic materials, hence viruses are divided into two major categories of DNA and RNA viruses. DNA viruses are mostly double-stranded, and RNA viruses are mostly single-stranded. Both double-stranded DNA or RNA have positive and negative strands. Some viral nucleic acids are divided into segments while some nucleic acids are infectious. Viruses are strictly parasitic in cells and can only reproduce in certain types of living cells. Once it infects a susceptible cell, however, a virus can direct the cell machinery to produce more viruses. The entire infectious virus particle, called a virion, consists of the nucleic acid and an outer shell of protein. The simplest viruses contain only enough RNA or DNA to encode four proteins. The most complex can encode 100 – 200 proteins. They are not sensitive to antibiotics while sensitive to interferon.

2.1 Classification and Characters of the Coronavirus Family

Coronaviruses are a type of sense single-stranded RNA virus that spreads between animals and humans, which can infect mammals and birds, causing digestive tract diseases in cattle and pigs or upper respiratory tract diseases in chickens. They have characteristic club-shaped spikes that project from their surface, which in electron micrographs create an image reminiscent of the solar corona, from which their name derives. They are about 80-120nm in diameter with a methylated cap structure at the 5' end of the genome, and a poly(A) tail at the 3’end. As the largest genome virus among the known RNA viruses, coronaviruses are enveloped single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses with genomes ranging from approximately 26 to 32 kilobases, and the group includes the largest known genomes among the RNA viruses. The coronaviruses form a subfamily within the family Coronaviridae of the order Nidovirales. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) has recognized four genera within the coronavirus subfamily: Alpha-coronavirus, Beta-coronavirus, and Gamma-coronavirus, which were previously referred to as coronavirus groups 1, 2, and 3, and Delta-coronavirus. Among them, β-Coronavirus can be divided into 4 lineages, A, B, C and D. Among the six known human coronaviruses (HCoVs), HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 belong to the genus Alpha Coronavirus while the rest belong to the genus Beta Coronavirus, of which HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1 belong to lineage A. For novel coronavirus, based on genome-wide molecular evolutionary genetic analysis, it shows that it belongs to the same β-coronavirus clade as SARS-CoV. Each virus particle is wrapped in a layer of protein “envelope”. All viruses basically do the same thing-invade cells, control certain components in cells to replicate themselves, and then infect other cells. So far, seven coronaviruses that can infect humans have been found. About one-fifth of the common cold is caused by four of the milder coronaviruses. Some coronaviruses are spread in specific animals. At least 20 years ago, all coronaviruses that could infect humans were relatively mild in nature, so the scientific community’s research on these viruses was also relatively stagnate.

2.2 Outbreaks of SARS and MERS

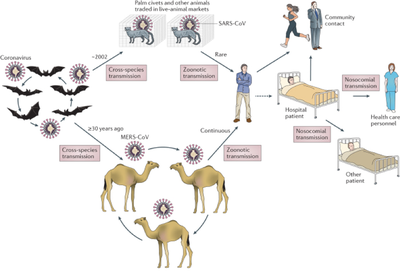

The three species that have emerged one after another in this century–SARS, MERS, and the COVID-19 are extremely serious, leading to large-scale outbreaks. In 2003, the pathogen that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in China was considered to be a brand-new coronavirus. This news shocked all researchers in related fields. It is believed that the outbreak of SARS was caused by a coronavirus that was originally transmitted between animals and was transmitted to humans through civet cats. A cross-host evolution research in 2005 suggested a rapid evolving process of viral proteins in civet, much like their adaptation in the human host in the early 2002-2003 epidemic. In 2012, a disease presenting with acute pneumonia and subsequent renal failure, symptoms similar to those for SARS, emerged in Saudi Arabia. A novel human coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was suspected to be responsible for this fatal disease. This new coronavirus spread from camels to humans, resulting in the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which once again confirmed that deadly coronaviruses can be passed from animals to humans.

2.3 Natural Sources of the Three Coronaviruses

The natural source of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV has been considered as civet cats and camels, respectively for a long time. However, in subsequent researches there was no evidence for the circulation of SARS-CoV-like viruses in palm civets in the wild or in breeding facilities. Rather, bats are the reservoir of a wide variety of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-like and MERS-CoV-like viruses. Different species of rhinolophid bats in China carry genetically diverse SARS-like coronaviruses, some of which are direct ancestors of SARS-CoV and hence have the potential to cause direct interspecies transmission to humans. Meanwhile, different coronavirus species closely related to MERS-CoV are circulating in bats. Bats are likely natural reservoirs of MERS-CoV or an ancestral MERS-like CoV. It is hypothesized that bat MERS-like CoV jumped to camels or some other as yet unidentified animal several decades ago. The virus evolved and adapted with accumulating mutations in camels and then was transmitted to humans very recently (Figure 2).

Prior to the outbreak of SARS and MERS, about 60 bat virus species had been reported. The number of identified bat viruses has dramatically increased since the initial SARS outbreak, and most are putative novel virus species or genotypes. The discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronavirus indicates that coronaviruses are highly connected to different bats species.

At the end of 2019, a previously unknown beta-coronavirus was discovered through the use of unbiased sequencing in samples from patients with pneumonia. Human airway epithelial cells were used to isolate a novel coronavirus, named 2019-nCoV. The 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) that is currently causing serious respiratory diseases worldwide has been officially named SARS-CoV-2, and the disease is COVID-19. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that 2019-nCoV falls into the genus beta-coronavirus, which includes SARS-CoV, bat SARS-like CoV, and others. The sequences obtained from five patients at an early stage of the outbreak are almost identical and share 79.6% sequence identity to SARS-CoV. Furthermore, 2019-nCoV is 96% identical at the whole-genome level to a bat coronavirus. Aside from bats origin possibility, pangolin-CoV is 91.02% and 90.55% identical to SARS-CoV-2 and BatCoV RaTG13, respectively, at the whole-genome level indicating that pangolin species are a natural reservoir of SARS-CoV-2-like CoVs. The source of the virus is inconclusive. However, by comparing the available genome sequence data for known coronavirus strains, available evidence illustrates that SARS-CoV-2 originated through natural processes and it is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.

3 Genome Analysis and Molecular Mechanisms

The rapid development of sequencing technology in recent years has brought biology into the era of big data. The width and quantity of biological data enables us to provide answers to many previously unresolved biological problems. Using bioinformatics and statistical technology, the genome analysis uncovers system biology information about the SARS-CoV-2, which explains biological phenomena or propose new hypotheses in multiple fields and levels.

3.1 Genome Analysis of SARS-CoV-2

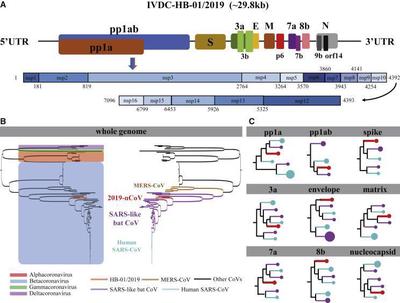

Suzhou Institute of Systems Medicine worked closely with CDC and after an in-depth annotation of the SARS-CoV-2 genome and comparison with similar coronaviruses revealed the genome composition of SARS-CoV-2 and the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak in 2003. There are significant differences between the protein sequences, which is expected to help researchers deeply understand the true origin and subsequent evolution of SARS-CoV-2, and provide a theoretical basis for subsequent prevention research. The researchers found that the new coronavirus encodes 16 non-structural proteins (nsp1-nsp16), 8 accessory proteins (3a, 3b, p6, 7a, 7b, 8b, 9b, and orf14) and 4 structural proteins (S, E, M and N) (Figure 3).

The genome-wide phylogenetic tree derived from molecular evolutionary genetic analysis shows that SARS-CoV-2 is in the same beta coronavirus evolution branch as human CoV, MERS-CoV, bat CoV, SARS-like bat CoV, and SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 is closer to SARS-like bat CoV in terms of the entire genome sequence, which is quite different from MERS-CoV. By systematically comparing the amino acid sequences of SARS-CoV-2 with SARS and SARS-like coronaviruses on each encoded protein, the research team found a total of 380 different amino acid positions between the two. Among them, 27 amino acid substitutions were found on the S protein (Spike) of the virus. These differences in protein levels may help to reveal the potential differences between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS viruses in infectivity and pathogenicity. Meanwhile, scientists from Chinese Academy of Sciences utilized the 93 complete SARS-CoV-2 genomes from the GISAID EpiFluTM database and the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in the past two months was studied. 120 replacement sites were found in 8 coding regions, of which 79 were non-synonymous substitutions, 40 were synonymous substitutions. The team also divided 58 haplotypes into 5 groups, of which 31 haplotypes came from Chinese patients and 31 came from other countries. At the same time, it was found that the genomic variation of SARS-CoV-2 is much lower than that of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.

3.2 Molecular components of SARS-CoV-2

There exists a methylated cap structure at the 5' end of the genome, and a poly(A) tail at the 3’end. The 5′-ends of eukaryotic cellular mRNAs possess a cap structure, in which an N7-methylguanine (m7G) moiety is linked to the first transcribed nucleotide by a 5′-5′ triphosphate bridge. This cap structure plays important roles in pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA export, RNA stability, translational initiation and escaping the recognition of the cellular innate immune system. Many viruses have evolved mechanisms for generating their own cap structures with methylation at the N7 position of the capped guanine and the ribose 2'-Oposition of the first nucleotide, which help viral RNAs escape recognition by the host innate immune system.

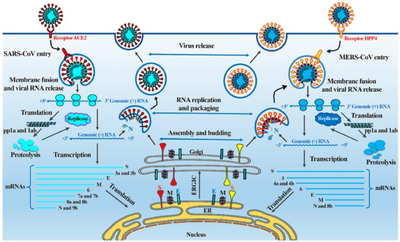

3.3 Molecular Mechanisms of Infection

Since coronaviruses cannot reproduce on their own, they have to hijack our cellular equipment to make copies of themselves. When the viruses reach the surface of cells, they uncover themselves by changing the physical appearance of the protein and mask with sugars or glycans. Then, the coronaviruses stretch out their protein spikes and use the shape of the protein to bind with the receptor on cells’ surface and get into the cell like a key and a lock. When they finally get inside the cell, they are free to release their genetical materials and begin to replicate themselves. Firstly, the host’s translation mechanism is hijacked and used to translate polyproteins and necessary viral proteases. Polyproteins (pp1a and pp1ab) are cleaved into 16 non-structural effector proteins by 3CLpro and PLpro, allowing them to form a replication complex with RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, which synthesizes full-length negative RNA strand templates. It is used to replicate the complete RNA genome and generate a single sub-genomic mRNA template for translation of viral structural proteins and auxiliary proteins. The newly synthesized structural proteins and accessory proteins are transported from the endoplasmic reticulum through the Golgi apparatus, and then new virus ions are accumulated in the budding Golgi vesicles. Finally, the mature SARS-CoV-2 virus is released from the host cell into the surrounding environment, repeating the infection cycle.

4 Key Protein with Structural Conformation Changes

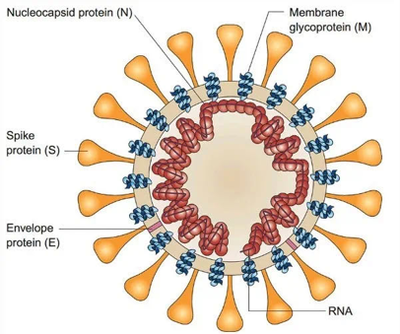

Coronavirus particles are composed of structural proteins and RNA: the outermost is Spike protein (S); then Envelope protein (E) and Membrane glycoprotein (M), assembled into virus particles Morphology; the innermost part is the nucleic acid substance RNA responsible for virus propagation, which is wrapped and protected by Nucleocapsid protein (N) (Figure 5). These proteins and RNA together form infectious virus particles that can cause disease.

4.1 Spike Protein and ACE Receptor as Essential Parts

The novel coronavirus, like the SARS-CoV in 2003, is also confirmed to enter human cells by recognizing the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2(ACE2) Receptor. ACE2 is the key for novel coronavirus invading the human body. Scientists found that in the process of SARS-CoV and novel coronavirus invading the human body, ACE2 is like a door handle, the virus grabs it, thus opening the door to enter the cell. The primary determinant of CoV tropism is the viral spike (S) entry protein. Trimers of the S glycoproteins on the virion surface accommodate binding to a cell surface receptor and fusion of the viral and cellular membrane. So, S protein is the key to understanding its infectivity, as well as to develop specific vaccines, therapeutic antibodies and precise diagnostic methods.

4.2 Structural Research on S Protein and ACE Receptor

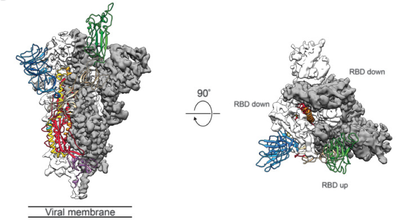

Using cryo-electron microscopy technology, it was found from the structure that one of the three receptor binding domains (RBD) of the novel coronavirus S protein would spiral upward, thereby allowing the S protein to form a space that can easily bind to the host receptor ACE2 conformation. In order to access the host cell receptor, the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the S protein undergoes a hinge-like conformational movement to hide or expose the key sites of receptor binding. This feature is similar to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but the RBD structure of the new coronavirus is closer to the center of the trimer. The RBD of single-chain S protein is in the 3.45 Å electron microscope structure, there are two different states: “down”-receptor unbound state; “up”-receptor bindable state, “up” structure is in a relatively unstable state. The structure contains three monomeric S proteins assembled into a trimer, and the RBD has a “top and bottom” conformation (Figure 6).

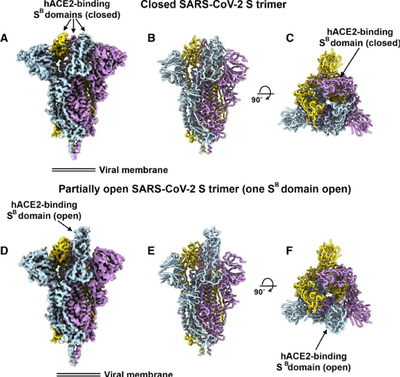

Through surface plasmon resonance technology (SPR) and negative staining EM, it has been functionally verified that according to SARS-CoV, the new coronavirus has higher affinity with ACE2. The affinity of the ACE2 protein with the new coronavirus is 10 to 20 times that of the SARS virus. The RBD domains of the new coronavirus are in the “three down” closed electron microscope structure and the “one up and two down” semi-open state. These structures further demonstrate the diversity of S protein trimer (Figure 7).

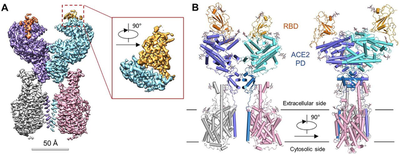

4.3 Discovery of Full-length Structure

Scientists from West Lake University, China disclosed the full-length structure of ACE2 and found that under the stability of the amino acid transport membrane protein B⁰AT1 in the intestine, ACE2 exists as a dimer, and its tail transmembrane region is tightly bound to B⁰AT1 protein. The researchers also observed two different conformations of ACE2, the activated “open” conformation and the non-activated “closed” conformation (Figure 8). This is the first time in the world to see the full picture of ACE2 at the atomic resolution level.

Subsequently, the same team once again released the 2.9 Å high-resolution electron microscope structure of the ACE2 and Sᴿᴮᴰ complex on bioRxiv, further demystifying the virus invading human cells. These research results provide a solid structural basis for the design of antibodies, small molecules and peptide drugs that disrupt the interaction between ACE2 and S protein.

5 Drug Discovery

Now scientists are stepping up research and development of special antiviral drugs. On the one hand, by revealing the molecular mechanisms of viral infection replication and analyzing the structure and function of key proteins, they provide drug targets that can be used for therapeutic intervention. On the other hand, through computer virtual screening, small molecules that bind to viral enzymes or receptors that have revealed structures or homologous modeling three-dimensional structures are used as potential lead compounds, and then concentrated on advantageous resources for activity verification. On top of that, cell-level screening of old drug libraries with high relevance and discovery of drug candidates with inhibitory effects on viral cell infections.

5.1 Protein Functions as Targets

There exist various drugs that were attempted to develop against the life cycle of coronavirus infection and replication, ranging from broad-spectrum antiviral strategies to coronavirus-specific strategies, such as coronavirus invasion, genome release, viral protein translation, viral RNA replication, viral assembly and viral release. Since no explicit drugs are proved to be the cure of SARS-CoV-2 and new synthetic drugs have not been discovered, drug repurposing seems to be a key solution and potential targets remain to be studied. Here a team lists potential targets, their roles in viral infection, and representative existing drugs or drug candidates that reportedly act on the corresponding targets in similar viruses and thus are to be assessed for their effects on SARS-CoV-2 infection.

5.1.1 3CLpro and PLpro

3CLpro and PLpro are two types of viral proteases. They play an important role in cleaving viral peptides into functional units and assisting the virus to replicate and package in the cell. Many anti-HIV drugs target this mechanism, such as Lopinavir and Ritonavir.

5.1.2 RdRp

RdRp is an RNA polymerase responsible for the synthesis of viral RNA. It can be blocked by existing antiviral drugs and drug candidates, including Remdesivir.

5.1.3 S protein

The interaction between the viral S protein and the host ACE2 receptor causes the cell to engulf the virus into the cell through endocytosis. The broad-spectrum antiviral drug Abidor is designed to prevent the virus from entering the host cell, and has produced curative effects in the treatment of influenza.

5.1.4 TMPRSS2

The TMPRSS2 protease produced by the host plays an important role in the proteolytic treatment of the S protein, and it can promote the binding of the S protein to the ACE2 receptor. In the in vitro test, the TMPRSS2 inhibitor Camostat Mesylate, which has been proven in clinical trials, is able to block the novel coronavirus from entering human cells.

5.1.5 ACE2 and AT2

In addition to being a receptor for the invasion of novel coronavirus, ACE2 also plays an important role in regulating blood pressure and fluid and electrolyte balance in the body. ACE2 catalyzes the degradation of angiotensin II to angiotensin. Angiotensin II acts to constrict blood vessels by binding to the AT1 receptor, while angiotensin acts to relax blood vessels by binding to the AT2 receptor. The balance between angiotensin II and angiotensin is crucial. Candidate drugs that target these targets may alleviate lung damage caused by the novel coronavirus.

5.2 Present Trials on SARS-CoV-2

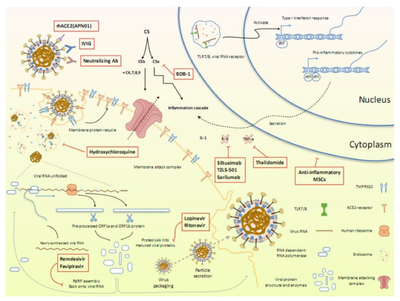

Apart from the drug candidates mentioned above, multiple clinical trials are already underway to evaluate the effects of other treatment options. More than 50 existing MERS and/or SARS inhibitors can be used to screen potential therapies for the treatment of new coronaviruses. Here, researchers summarize the ongoing therapeutic options that may lead us to combating the novel pathogen (Figure 9).

5.3 Computer-aided Drug Design (CADD)

New drug development costs a lot and in order to improve the efficiency of drug R&D (Research and Development), shorten the R&D cycle, and save R&D costs, it is particularly important to use reasonable drug design methods. Among them, the use of computer-aided drug design for drug screening can improve the drug discovery hit rate. Computer-aided drug design (CADD), based on mathematics, medicinal chemistry, biochemistry, molecular biology, structural chemistry, and other disciplines, with quantum chemistry, molecular mechanics, etc. as the theoretical basis, with the help of computer numerical calculation and logical judgment, databases, graphics Learning and artificial intelligence and other processing technologies for rational drug design. Computer-aided drug discovery has been widely used in almost every stage of the drug discovery and development workflow. In the past few decades, computational drug discovery methods such as molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling and mapping, de novo design, molecular similarity calculation, and sequence-based virtual screening have been greatly improved. These methods are roughly divided into a target structure-based method and a ligand structure-based method. Methods based on target structure include ligand docking, pharmacophore and ligand design methods. The ligand-based method uses only ligand information to predict activity, depending on its similarity/dissimilarity to previously known active ligands. To combat the new coronavirus, researchers also use computer-aided drug design techniques to quickly find potential antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2.

5.3.1 Screening for Potential Drug Molecules

A number of virtual screening of existing drug small molecules based on the three-dimensional structure model of SARS-CoV-2 protein has been conducted. Researchers in China have discovered four small molecule drugs which can bind the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 through high-throughput screening with 8000 candidates in clinical drug databases; Researchers in USA developed SBDR based on machine learning and mathematical methods. The model screened 1,465 drugs and found that many FDA approved drugs have the potential to combat against SARS-CoV-2.

5.3.2 Allosteric Drug Design

The viral entry and associated infectivity stems from the formation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein complex with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2(ACE2). The detection of putative allosteric sites on the viral spike protein molecule can be used to elucidate the molecular pathways that can be targeted with allosteric drugs to weaken the spike-ACE2 interaction and thus, reduce viral infectivity. Due to the complexity of SARS-CoV-2 structures, targeting protein-protein interactions at allosteric sites and hotspots (key binding sites) have become an essential strategy in drug discovery. In allosteric drug design, the identification of ligand-binding pockets, especially the locations and the drug ability of allosteric sites, is critically important. Accordingly, a variety of computational methods have been developed for detecting allosteric pockets based on sequence, structure and dynamics. By combining sequence information and molecular dynamics calculation, surface and interior allosteric sites could be identified. In particular, these surface allosteric sites are always corresponding to interfacial residues when the protein complex is formed. An international cooperation applied tools consisted of the protein contact networks (PCNs), SEPAS (Affinity by Flexibility), and perturbation response scanning (PRS) based on elastic network modes to the ACE2 complex with SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV spike proteins. All the analysis used converged towards a specific region (allosteric regulatory region [AMR]), which is present in both complexes and is expected to serve as an allosteric site that regulates the binding of nail proteins to ACE2. Preliminary results of hepcidin (a molecule with a strong structure and sequence of AMR) showed that the binding affinity of spike protein to ACE2 protein was inhibited. Thus, hepcidin could be a potential solution for COVID-19.

5.3.3 Protein-protein Interactions (PPIs) Related Drug Design

In a new study, 26 SARS-CoV-2 proteins were cloned, labeled and expressed in human cells. By affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS), 332 highly reliable SARS-CoV-2 and human protein-protein interactions (PPIs) were identified (Figure 10).

Drug discovery based on PPIs in different dimensions, from the enumeration of allosteric mechanism to the identification of allosteric pockets counts for possible drug target identification. For each SARS-CoV-2 viral protein, the researchers performed gene ontology enrichment analysis and found that the SARS-CoV-2 viral protein is connected to a wide range of cell biological processes in the human body, including: DNA replication (Nsp1), epigenetics and gene expression regulation (Nsp5/8/13; E), vesicle transport (Nsp6/7/10/13/15; Orf3a/8; E), lipid modification (S) , RNA processing and regulation (Nsp8; N), ubiquitination regulation (Orf10), signal transduction (Nsp8/13; N; Orf19b), nuclear transport mechanism (Nsp9/15; Orf6), cytoskeleton (Nsp1/13) , Mitochondria (Nsp4/8; Orf9c) and extracellular matrix (Nsp9), etc. In addition, the researchers also confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins also have extensive interactions with the body’s natural immune signaling pathways. Using systematic chemical drug search and network analysis, the researchers found 69 drugs that are expected to be used for the treatment of COVID-19, of which 27 are FDA approved drugs, 14 are new drugs under clinical research and 28 preclinical drug candidates. It is worth noticing that certain proteins that interact with SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins can be targeted by some drugs, and even some drugs have become candidates for the treatment of COVID-19, such as chloroquine. Besides, the researchers also pointed out that azithromycin has off-target activity against human mitochondrial ribosomes, which interact with SARS-CoV-2 Nsp8 protein. Therefore, antibiotics such as azithromycin may also be used to treat COVID-19.

5.3.4 Artificial Intelligence Related Drug Design

A team utilized their pre-trained deep learning-based drug-target interaction model MT-DTI (Molecular Transformation-Drug Target Interaction) to figure out potential drug targeting at SARS-CoV-2 viral protein. MT-DTI is a deep learning model based on self-attention, used to predict the affinity score between drugs and proteins without relying on the three-dimensional structure of the protein. The results show that the antiretroviral drug atazanavir used to treat and prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the most promising compound and Kaletra (Lopinavir/ritonavir combination) can also be used to treat COVID-19. The application of machine-learning in combating new coronaviruses emerges as the influence of ever-rising artificial intelligence. The evolution of machine intelligence now provides a guide for early-stage drug design and discovery in the current big data era, which makes medical services more efficient and propose a new possibility for short time drug design.

6 Discussion

In recent months, with the unremitting efforts of the majority of clinical and basic scientific researchers, from the discovery of the genome of the novel coronavirus to the development of a variety of molecular tests, the laboratory detection of the SARS-CoV-2 has made rapid progress in a short time. At present, the common methods used in virologic diagnosis include: virus isolation and culture, immunological technology and molecular biology technology which contains nucleic acid molecule hybridization, PCR, nucleic acid sequencing, etc. The current detection volume has been able to meet the needs of nucleic acid testing in a short time, which is why universal testing has been implemented in Wuhan and some areas of Beijing. At the same time, there has been a new breakthrough and progress in vaccine research and development. After the vaccine is injected, there are two ways to achieve the effect: humoral immunity via antibodies produced by B cells, especially neutralizing antibodies and cellular immunity via CD8+ effector T cells. Professor Wei Chen and her team’s findings suggest that the Ad5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine warrants further investigation. In their clinical experiments, specific T-cell response peaked at day 14 post-vaccination which indicates the promising application prospect. In a latest research, N terminal domain (NTD) is proved to be a new therapeutic target on SARS-CoV-2 S protein. It is reported that a human monoclonal antibody 4A8 can recognize and bind to the NTD epitope on SARS-CoV-2 S protein, exert neutralizing activity and can be used as a potential therapeutic monoclonal antibody, and its mechanism of action is independent of the body binding mechanism. The combination of 4A8 and receptor binding domain (RBD) targeting antibody can prevent the virus from producing drug resistance mutations and escape, and is expected to become a “cocktail” therapy. Something interesting in treating COVID-19 also deserves more attention. A study analyzed the clinical data of thousands of patients with COVID-19 and showed that the novel coronavirus invades the receptor of ACE2 in human cells, and the concentration in the blood of men is higher than that of women. This will help explain why men are more susceptible to novel coronavirus. In addition, potential drugs have been widely used in clinical applications. In June, a team from Oxford declared that low-cost dexamethasone reduces death by up to one third in hospitalized patients with severe respiratory complications of COVID-19. For the first time, one drug was shown to improve survival in COVID-19 even though the supporting evidence is weak. Various drug candidates selected by multiple methods have been utilized in clinical trials and no convincing results has been made. Thus, more in-depth research and innovative strategies need to be conducted for possible drug discovery. Similarly, referring to the protein-protein interaction network between humans and SARS-CoV-2, drug developers can quickly find possible drug candidates for COVID-19. At the same time, targeted biochemical and structural research helps to understand the virus-host complex more deeply, which also provides important information for the design and development of COVID-19 special effects.

Reference

- Almeida JD, Berry DM, Cunningham CH, Hamre D, Hofstad MS, Mallucci L, McIntosh K, Tyrrell DA (November 1968). “Virology: Coronaviruses”. Nature. 220 (5168): 650. Bibcode:1968Natur.220..650..

- Woo PC, Huang Y, Lau SK, Yuen KY. Coronavirus genomics and bioinformatics analysis. Viruses. 2010;2(8):1804-1820.

- Adams MJ, Carstens EB. Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2012). Arch Virol. 2012;157(7):1411-1422.

- Kuiken T, Fouchier RA, Schutten M, et al. Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;362(9380):263-270.

- Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1967-1976.

- Song HD, Tu CC, Zhang GW, et al. Cross-host evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in palm civet and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(7):2430-2435.

- Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 25;369(4):394]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1814-1820.

- van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Lauber C, et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. mBio. 2012;3(6):e00473-12. Published 2012 Nov 20.

- Alagaili AN, Briese T, Mishra N, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia [published correction appears in MBio. 2014;5(2):e01002-14. Burbelo, Peter D [added]]. mBio. 2014;5(2):e00884-14. Published 2014 Feb 25.

- Wang LF, Shi Z, Zhang S, Field H, Daszak P, Eaton BT. Review of bats and SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1834-1840.

- Hu B, Ge X, Wang LF, Shi Z. Bat origin of human coronaviruses. Virol J. 2015;12:221. Published 2015 Dec 22.

- de Wit E, van Doremalen N, Falzarano D, Munster VJ. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(8):523-534.

- Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181-192.

- Hu B, Zeng LP, Yang XL, et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(11):e1006698. Published 2017 Nov 30.

- Sama IE, Ravera A, Santema BT, et al. Circulating plasma concentrations of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in men and women with heart failure and effects of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibitors. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1810-1817.

- Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310(5748):676-679.

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727-733.

- Tan WJ, Zhao X, Ma XJ, et al. A novel coronavirus genome identified in a cluster of pneumonia cases — Wuhan, China 2019−2020. China CDC Weekly 2020;2:61-62.

- Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270-273.

- Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z. Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak [published correction appears in Curr Biol. 2020 Apr 20;30(8):1578]. Curr Biol. 2020;30(7):1346-1351.e2.

- Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):450-452.

- Wu A, Peng Y, Huang B, et al. Genome Composition and Divergence of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Originating in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27(3):325‐328.

- Yu WB, Tang GD, Zhang L, Corlett RT. Decoding the evolution and transmissions of the novel pneumonia coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 / HCoV-19) using whole genomic data. Zool Res. 2020;41(3):247‐257.

- Shatkin AJ. Capping of eucaryotic mRNAs. Cell. 1976;9(4 PT 2):645-653.

- Nallagatla SR, Toroney R, Bevilacqua PC. A brilliant disguise for self RNA: 5'-end and internal modifications of primary transcripts suppress elements of innate immunity. RNA Biol. 2008;5(3):140-144.

- Darnell JE Jr. Transcription units for mRNA production in eukaryotic cells and their DNA viruses. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1979;22:327-353.

- Chen Y, Guo D. Molecular mechanisms of coronavirus RNA capping and methylation. Virol Sin. 2016;31(1):3-11.

- Liu C, Zhou Q, Li Y, et al. Research and Development on Therapeutic Agents and Vaccines for COVID-19 and Related Human Coronavirus Diseases. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6(3):315-331.

- Fehr AR, Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1-23.

- Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):11. Published 2020 Mar 13.

- Song Z, Xu Y, Bao L, et al. From SARS to MERS, Thrusting Coronaviruses into the Spotlight. Viruses. 2019;11(1):59. Published 2019 Jan 14.

- Zumla A, Chan JF, Azhar EI, Hui DS, Yuen KY. Coronaviruses - drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(5):327-347.

- Jeffers SA, Tusell SM, Gillim-Ross L, et al. CD209L (L-SIGN) is a receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(44):15748-15753.

- Liu Z, Zheng H, Lin H, et al. Identification of common deletions in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 22]. J Virol. 2020;JVI.00790-20.

- Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581(7807):221-224.

- Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367(6483):1260-1263.

- Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281-292.e6.

- Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444-1448.

- Yan, R., et al. Structural basis for the recognition of the 2019-nCoV by human ACE2.

- Maxmen A. More than 80 clinical trials launch to test coronavirus treatments. Nature. 2020;578(7795):347-348.

- Sheahan TP, Sims AC, Leist SR, et al. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):222. Published 2020 Jan 10.

- Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269-271.

- Guo D. Old Weapon for New Enemy: Drug Repurposing for Treatment of Newly Emerging Viral Diseases [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 11]. Virol Sin. 2020;1-3.

- Kadam RU, Wilson IA. Structural basis of influenza virus fusion inhibition by the antiviral drug Arbidol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(2):206-214.

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271-280.e8.

- De Witt BJ, Garrison EA, Champion HC, Kadowitz PJ. L-163,491 is a partial angiotensin AT(1) receptor agonist in the hindquarters vascular bed of the cat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;404(1-2):213-219.

- Li G, De Clercq E. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(3):149-150.

- Sarma P, Prajapat M, Avti P, Kaur H, Kumar S, Medhi B. Therapeutic options for the treatment of 2019-novel coronavirus: An evidence-based approach. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52(1):1-5.

- Tu YF, Chien CS, Yarmishyn AA, et al. A Review of SARS-CoV-2 and the Ongoing Clinical Trials. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7):2657. Published 2020 Apr 10.

- Li et al, Therapeutic Drugs Targeting 2019-nCoV Main Protease by High-Throughput Screening.

- Nguyen el al, Potentially highly potent drugs for 2019-nCoV.

- Belouzard S, Millet JK, Licitra BN, Whittaker GR. Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses. 2012;4(6):1011-1033.

- Cukuroglu E, Engin HB, Gursoy A, Keskin O. Hot spots in protein-protein interfaces: towards drug discovery. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2014;116(2-3):165-173.

- Clarke D, Sethi A, Li S, et al. Identifying Allosteric Hotspots with Dynamics: Application to Inter- and Intra-species Conservation. Structure. 2016;24(5):826-837.

- Liang Z, Zhu Y, Long J, Ye F, Hu G. Both intra and inter-domain interactions define the intrinsic dynamics and allosteric mechanism in DNMT1s. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:749-764. Published 2020 Mar 23.

- Perricone U, Gulotta MR, Lombino J, et al. An overview of recent molecular dynamics applications as medicinal chemistry tools for the undruggable site challenge. Medchemcomm. 2018;9(6):920-936. Published 2018 Apr 19.

- Nussinov R, Tsai CJ. The different ways through which specificity works in orthosteric and allosteric drugs. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(9):1311-1316.

- Csermely P, Nussinov R, Szilágyi A. From allosteric drugs to allo-network drugs: state of the art and trends of design, synthesis and computational methods. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13(1):2-4.

- Di Paola L, Giuliani A. Protein contact network topology: a natural language for allostery. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;31:43-48.

- Hadi-Alijanvand H. Complex Stability is Encoded in Binding Patch Softness: a Monomer-Based Approach to Predict Inter-Subunit Affinity of Protein Dimers. J Proteome Res. 2020;19(1):409-423.

- Atilgan C, Atilgan AR. Perturbation-response scanning reveals ligand entry-exit mechanisms of ferric binding protein. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(10):e1000544.

- Di Paola, Luisa & Giuliani, Alessandro. (2020). Mapping active allosteric loci SARS-CoV Spike Proteins by means of Protein Contact Networks.

- Di Paola L, Hadi-Alijanvand H, Song X, Hu G, Giuliani A. The discovery of a putative allosteric site in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by an integrated structural/dynamical approach [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 17]. J Proteome Res. 2020;10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00273.

- Liang Z, Zhu Y, Liu X, Hu G. Role of protein-protein interactions in allosteric drug design for DNA methyltransferases. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2020;121:49-84.

- Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, et al. A SARS-CoV-2-Human Protein-Protein Interaction Map Reveals Drug Targets and Potential Drug-Repurposing. Preprint. bioRxiv. 2020;2020.03.22.002386. Published 2020 Mar 22.

- Wen M, Zhang Z, Niu S, et al. Deep-Learning-Based Drug-Target Interaction Prediction. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(4):1401-1409.

- Beck BR, Shin B, Choi Y, Park S, Kang K. Predicting commercially available antiviral drugs that may act on the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) through a drug-target interaction deep learning model. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:784-790. Published 2020 Mar 30.

- Chen H, Engkvist O, Wang Y, Olivecrona M, Blaschke T. The rise of deep learning in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2018;23(6):1241-1250.

- Jing Y, Bian Y, Hu Z, Wang L, Xie XQ. Deep Learning for Drug Design: an Artificial Intelligence Paradigm for Drug Discovery in the Big Data Era [published correction appears in AAPS J. 2018 Jun 25;20(4):79. Xie XS [corrected to Xie XQ]]. AAPS J. 2018;20(3):58. Published 2018 Mar 30.

- Sheridan C. Coronavirus and the race to distribute reliable diagnostics. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(4):382-384.

- Zhu FC, Li YH, Guan XH, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine: a dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, first-in-human trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10240):1845-1854.

- Chi X, Yan R, Zhang J, et al. A neutralizing human antibody binds to the N-terminal domain of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 22]. Science. 2020;eabc6952.